F51

Armchair for the

directors room at

the Bauhaus Weimar

Bauhaus Original

1922/23

F51

Ground-breaking cube

Frame

Solid ash, natural, black or white lacquered, solid walnut or solid oak

Cushion

Fabric or leather

Dimensions (cm)

Width: 70

Depth: 70

Height: 70

Seat height: 42

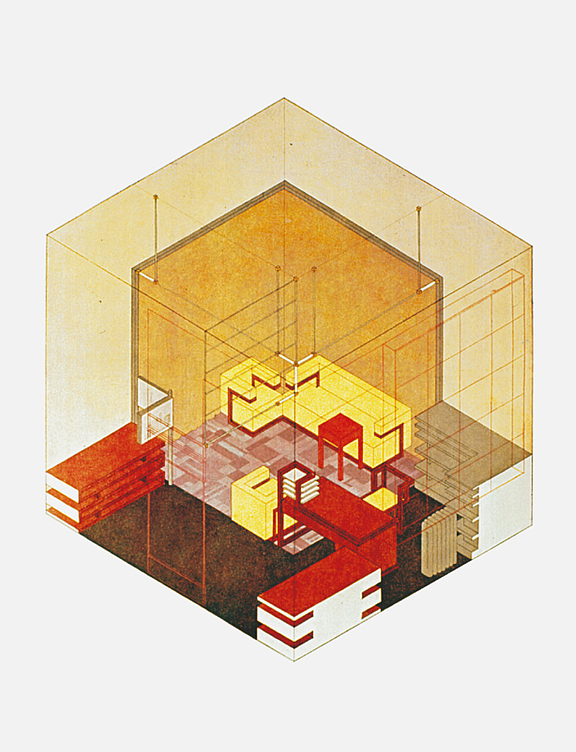

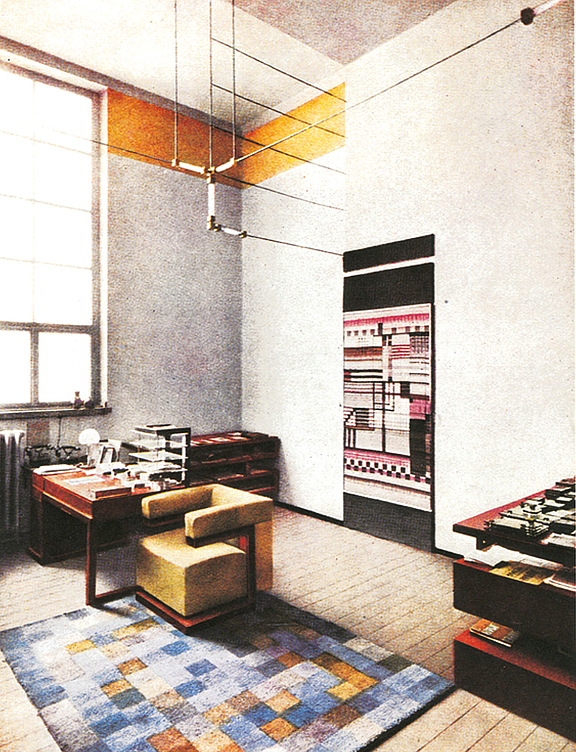

We are in the arcanum of modernism. The F51 (1920) is not just any armchair, it is the iconic armchair for the director's room in the Weimar Bauhaus. Walter Gropius had already injected his modernist dynamic into the building and created a small holistic work of art, encompassing interiors and furniture, tapestry and ceiling lamp. Nothing is randomly chosen and everything is connected. If you study the isometric layout of the director's room you can see the furniture as part of a three-dimensional coordinate system.

All major designers, including Mart Stam, have walked through this central room of the Bauhaus in Weimar. Consciously or unconsciously, they were already influenced by the overarching ideas of the F51 armchair. Its protruding armrests can be seen as a precursor of Mart Stam’s chairs without back legs and anticipate Marcel Breuer’s stool on runners (1925).

“The first cantilever chair concept is from Walter Gropius, the first cantilever armrest architecture from El Lissitzky,” says Tecta’s Axel Bruchhäuser. Walter Gropius’ own thoughts: The goal of modern architecture is “to defy gravity and overcome the earth’s inertia in impression and appearance.” This later became the intellectual root of the cantilever principle and the creed of the collection in Tecta’s Cantilever Chair Museum in Lauenförde.

Despite its cubic form, the chair has an almost human appearance with its heavy but floating upholstery and simple frame. With the F51 Gropius has made a piece of space around us tangible and given it a geometric shape. It seems as if the architect had intermeshed two C-shaped elements in such a way that they continue to convey suspense. The projecting frame lifts the back of the seat and armrest upholstery away from the floor. Calm and dynamism – the armchair radiates both simultaneously and thus points to the architect’s future-forward design approach, which radically questioned all things traditional.

In 1926 Gropius wrote emphatically in his “Principles of Bauhaus Production”: “It is only through constant contact with constantly evolving techniques, with the discovery of new materials and with new ways of putting things together that the creative individual can learn to bring the design of objects into a living relationship with tradition.” The intricately crafted F51 armchair is a case in point. Existing elements are reinterpreted and the construction, the “crafted” elements are openly revealed.

Founder and thinker of the Bauhaus philosophy. The architect and founder of the Bauhaus, Walter Gropius (1883-1969), mocked traditional architecture as “salon art”. He descended from a family of great builders: his great uncle was Martin Gropius. Walter Gropius abandoned his architectural studies and initially joined the office of Peter Behrens – as had, incidentally, Adolf Meyer, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. A short time later, Gropius founded what we now call modernism – a major break from and with the conventions of the past.

One key feature was that he did not reject the principles of the industrial age – standardisation and prototypes – but made them productive tools for his work. “A resolute affirmation of the living environment of machines and vehicles,” wrote the Bauhaus director in 1926, who believed that “the creation of standard types for all practical commodities of everyday use is a social necessity.” This spirit not only gave rise to the Fagus factory as an icon of modern architecture and the Dessau Bauhaus, but also laid the foundations of what is still a driving force for us today.

“The objective of creating a set of standard prototypes which meet all the demands of economy, technology, and form, requires the selection of the best, most versatile, and most thoroughly educated men who are well grounded in workshop experience and who are imbued with an exact knowledge of the design elements of form and mechanics and their underlying laws.”

By founding the Bauhaus, Gropius launched a new school of thought, opposing the traditional architecture of which he was so critical. In 1919 Gropius was appointed director of the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar, Thuringia, and named the new school “State Bauhaus Weimar”.

Gropius’ driving vision was not only to construct a “building of the future” and a holistic work of art, but also the highly modern approach of maintaining the distinction between apprentice and master while intermeshing the two teachings in a novel manner. To work across the disciplines, with an interdisciplinary approach in the spirit of research and experimentation.

Gropius also knew how to translate architectural concepts into furniture design, exemplified by his unique penetration of volume and linearity that characterises many of his works. Walter Gropius directed the Bauhaus until its closure in 1933, emigrated to England in 1934 and to Cambridge, USA, in 1937 to teach as professor of architecture at Harvard University.

Bauhaus

Reinterpretation