L61

Saturn desk lamp

Bauhaus Original

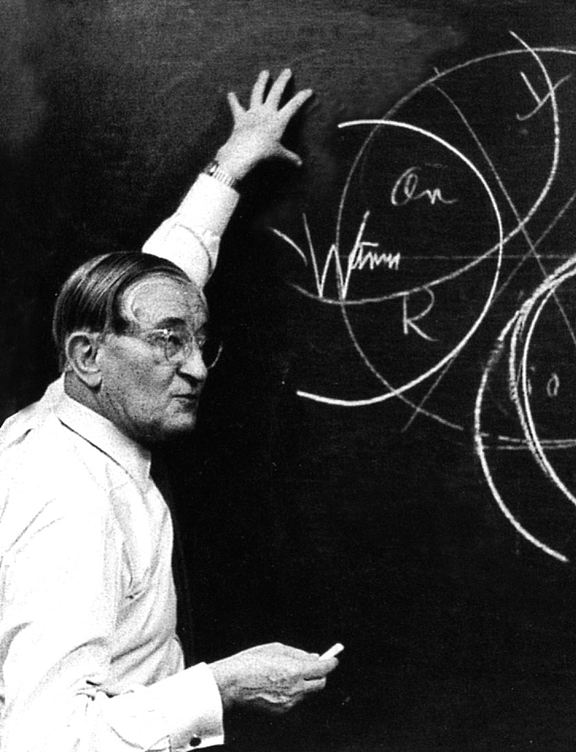

Josef Albers

1926

L61

Glowing economy of form

Frame

Chromed sheet steel, crystal glass foot, fabric-coated cord

Socket

E27, mirrored bulb 60 W

Dimensions (cm)

ø: 24

Height: 40

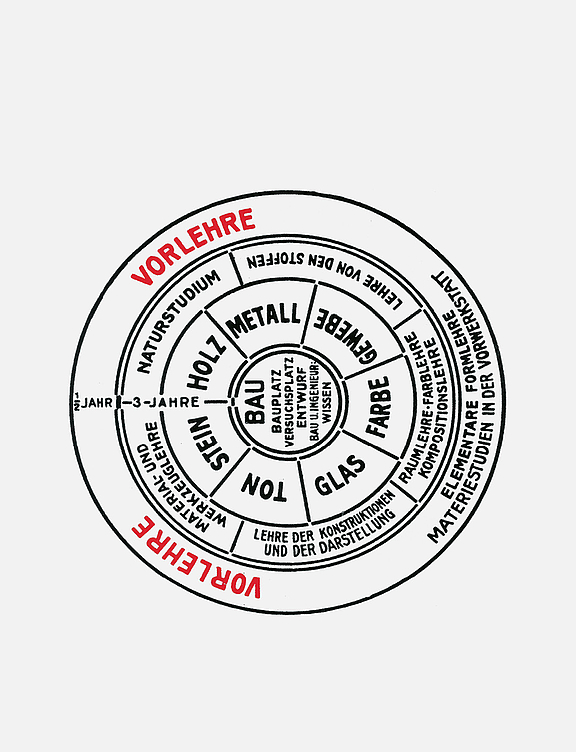

The famous preliminary course taught by Walter Gropius and Josef Albers, a basic training lasting around one year that allowed students to experiment freely with colours, shapes and materials, was an essential part of the Bauhaus apprenticeship. Josef Albers (1888-1976) already displayed an extraordinary artistic talent at a young age, so that Walter Gropius appointed him as a junior master even before his final apprenticeship exam. From surface to space – this experimental approach later became one of the key assignments in Joseph Albers' Bauhaus preliminary course.

The concentric circles of the 1926 Saturn lamp are based on this precept. One of his best-known students was Ati Gropius, Walter Gropius’ daughter, who supported Tecta's work constructively for decades.

The Saturn desk lamp constituted a fundamental design with nothing wasted, based on the design principles of the Bauhaus master and his concept of “economy of form”. A further challenge by Josef Albers in 1926: “How can I create a beautiful three-dimensional structure out of a piece of paper with nothing wasted?”

Tecta had initially conceived “Saturn” as a pendant lamp based on a design by student Arieh Sharon from 1926. The desk lamp followed in 1998.

Until this very day, the three-dimensional sculpture of the SATURN lamp is produced by laser cutting in Lauenförde out of flat two-dimensional sheet steel – still distinctively with nothing wasted.

The lamp glows like a candle, creating a festive atmosphere. It uses a minimum of material and underlines the lighting philosophy with its streamlined sheet steel. Both the desk and pendant versions are licensed by the label of the Bauhaus Archives.

“In art 1+1 sometimes equals three.” This quote by Josef Albers is written on the lamp’s little pendant.

And is complemented by Mies van der Rohe's words: “God is in the details.”

Born in Bottrop, Josef Albers explored and experimented with shapes and colours in their artistic dimension and visual perception like no other. Josef Albers started training as a primary school teacher in 1905. From 1919 to 1920 he studied in Franz von Stuck’s painting class at the Royal Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. In 1920 he went to Weimar. Among other things, Albers enrolled in the preliminary course taught by Johannes Itten and attended the glass painting workshop. Despite his young age, Josef Albers stood out for his exceptional talent. Walter Gropius appointed him as a junior master even before his final apprenticeship exam, and to the Bauhaus teaching staff in 1923.

Josef Albers directed the famous preliminary course, a basic training lasting around one year which allowed students to experiment freely with colours, shapes and materials. He developed a ground-breaking approach to teaching art, embracing the Bauhaus philosophy according to which the laws of artistic activity must be developed from the object’s function and material. Walter Gropius appointed him as a junior master in 1925.

From 1925 to 1927-1928 he directed the preliminary course at Bauhaus Dessau together with László Moholy-Nagy. After Nagy’s departure in 1928, Albers became the sole director of the preliminary course and head of the carpentry workshop until 1929.

When the Bauhaus was closed down in 1933, Albers and his wife Anni, a former Bauhaus student whom he had married in 1925, emigrated to the USA. Albers was appointed to a position at Black Mountain College in Asheville. There he taught art, and his extraordinary teaching style attracted young artists such as Donald Judd, Willem de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg. From 1936 Albers held numerous guest professorships worldwide. His philosophy was: “art is to present vision first, not expression first.”

Many famous works originate from Albers’ Bauhaus period – glass paintings, designs for furniture and everyday objects. His artistic works were distinguished with numerous awards. Albers was awarded a total of fourteen honorary doctorates in the United States, Canada and Europe.