F41-E

Liege auf Rädern

Breuer-couch on wheels

Marcel Breuer

1928

F41-E

The Mobile Manifesto

Frame

Stainless steel, matt polished, nickel-plated wheels

Seat and back

Double woven wickerwork

Bauhaus-straps

Made of durable fabric "Outdoors", 40 colours

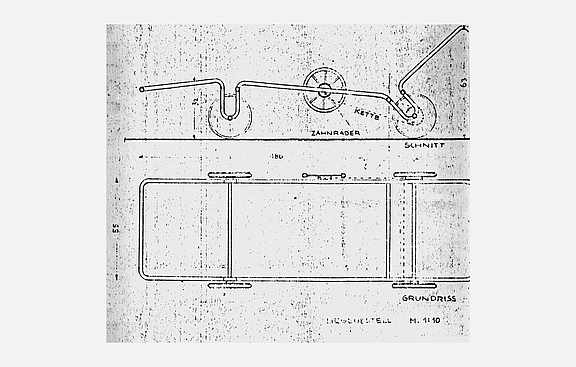

Dimensions (cm)

Width: 186

Depth: 61

Height: 63

Seat height: 30

Marcel Breuer staunchly followed his principles in everything he did. The head of the Bauhaus furniture workshop already had a predilection for cycling and lightweight construction. So, he took it a step further. After the world of heavy furniture had started its decline there was no stopping him. Around 1928, Breuer sketched an idea of combining a bicycle and armchair into a lounge on wheels – what a wonderfully crazy inspiration! For over half a century it was never realised, until TECTA added the mobile lounge to its product range in 1984, as an outdoor vehicle that allows you to lie back on its wicker surface in the open air and follow the light reflected by its metal frame.

The result was not a banal lounge on wheels, but rather a mobile manifesto. An ethereal sculpture, almost too beautiful to sit on. While futurism worshipped speed in martial words: “A racing car, its frame adorned with great pipes, like snakes with explosive breath ...,” Breuer’s approach to movement was almost meditative. And he created a piece of furniture that abolishes the polarity between relaxation and motion.

Anyone who sees the delicate wicker surface of the lounge, its matt stainless steel frame and hard-wearing Bauhaus straps, will discover a mobile sculpture for domestic use that looks perfectly contemporary.

Perfection of construction and detail. Of course, the first thing we associate with Bauhaus master Marcel Breuer is one material: tubular steel. And one principle: the cantilever chair, which sparked modern furniture design. “Humankind was freed from the tethers of rigid sitting to enjoy the freedom of the floating seat. The cantilever chair was a symbol of its time.” But this does not really do justice to Marcel Lajos (“Lajkó”) Breuer (1902-1981). What he really pursued was research into the essence of objects: what should, what can a modern piece of furniture do today, was the Bauhaus question.

In 1925, Breuer became head of the furniture workshop in Dessau as a “junior master”. The year before, he had already postulated his definition of contemporary furniture. Although he attached great importance to details, Breuer favoured the precision of thinking over formal aspects. “There is the perfection of construction and detail, along with and in contrast to simplicity and generosity in form and use,” he wrote in an essay outlining his philosophy.

His role in popularising tubular steel for furniture design may also be due to his being one of the first to realise how dynamic our lives had become, demanding equally light and flexible solutions. The cycling enthusiast also embraced the latest trends in architecture, industry and design for a new zeitgeist. “I have specifically chosen metal for these pieces of furniture to achieve the characteristics of modern spatial elements,” explained Breuer. “The heavy upholstery of a comfortable armchair has been replaced by tightly stretched fabric surfaces and a few lightweight springy cylindrical brackets.”

In addition, the construction was no longer hidden, but flashing chrome became a visible part of the design. Cantilever chairs were bolted, not welded, functions stacked and colour-coded. The result was a dematerialised floating appearance and a new spirit of space. The cantilever chair meant a liberation from the thousand-year-old model of rigid throne-like sitting. It was the implementation of the functional, kinetic and constructive counter-principle. This kinetic line, the dawn of the modern era, can still be traced to the young Bauhaus designers today.