D62

Pressa-armchair

Bauhaus Original

El Lissitzky

1928

D62

Architecture that rolls, swims and flies

Frame

Upholstery, lacquered, red, black, white or blue

Cushion

Loose cushion in fabric or leather

Dimensions (cm)

Width: 75

Depth: 63

Height: 71

Seat height: 43

Variant D62E

Stainless steel high gloss slick

In 1926 the architect, photographer, designer, graphic artist and painter postulated: “The static architecture of the Egyptian pyramid has been overcome: our architecture rolls, swims, flies. It will sway and float in the air. I want to help invent and form this new reality.” The constructivist created pictorial compositions and layouts that push the boundaries of the familiar. This energy could be felt in numerous projects and pavilions – and is also to be found in this seating sculpture.

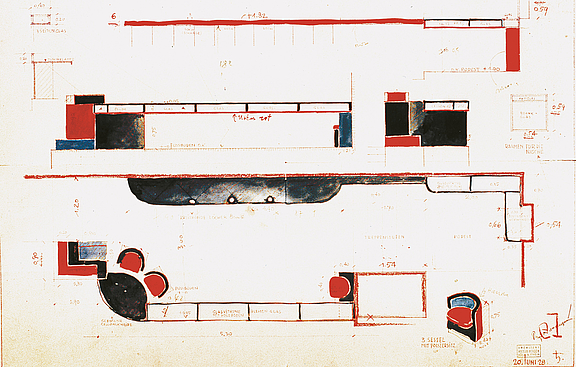

The conical club chair looks incredibly modern and could well have been created a half century later, in the late 1970s. In fact, El Lissitzky designed the armchair as early as 1928 for the Soviet pavilion at the International Print and Press Exhibition “Pressa” in Cologne. It was part of the presence of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, an element of a holistic work of art with a monumental, factory-like pavilion, its interior packed with photos, typography and installations.

In contrast, the D62 armchair exudes calm. The constructivist architect plays with two views and two opposing materials: a hard, thin but flexible shell and a ‘soft’, comparatively voluminous centre. The object is supported by a stretched wooden frame out of maple or beech, its cone shape encompassing a rather luxuriant leather upholstery for the back and seat, reaching down to the ground. It almost feels like standing in front of a crustacean with a hard shell and radiantly soft centre that invites you to take a seat.

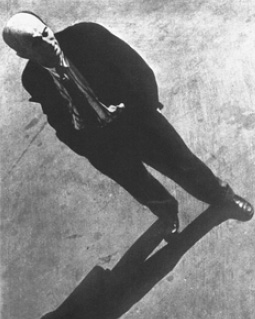

The visionary constructor. Universal artist El Lissitzky (1890-1941) is one of the key protagonists of constructivism. The architect, photographer, designer, graphic artist and painter first studied architecture at Darmstadt Technical University (1909-14) and in Moscow (1914-18), and then followed Marc Chagall’s invitation to teach at Witebsk Art School, where he met Kazimir Malevich. Lissitzky liked to call himself a “constructor”.

Filled with enthusiasm for the precision of science and modern engineering, he went on to create geometric-abstract works of art (“prouns” = innovation-establishing projects), which seem to float weightlessly in space. One famous example, which was never realised, was his “floating, horizontal skyscraper” from 1924/25 named “wolkenbügel” (cloud irons), a title that may have been inspired by Hans Arp. The “cloud irons” were El Lissitzky’s contribution to modernising the city, a prototype that could be used anywhere to emphasise landmarks.

At the same time, the “cloud irons” became an icon of modernity and their creator was to prove right: “Only inventions will determine form creation.” The cloud irons and their cantilever construction also influenced the development of the cantilever chair, based on a new spirit of the times: floating and flying.

As a creator, the constructivist El Lissitzky had a major impact on the avant-garde of the 1920s. His Lenin Tribune, which seems to hover over the ground in an expansive steel construction – inspired by Lenin’s outstretched hand in his propaganda speeches – is unforgotten.

Tecta’s collaboration with Lissitzky’s widow and son Jen dates back to 1978 and started with a curved plywood chair, originally designed for the 1930 Hygiene Exhibition in Dresden. This marked the beginning of a series of joint explorations and discoveries.