F51-3

Gropius-Sofa, 3-seater

Bauhaus Original

Walter Gropius

1920

F51-2

Defying gravity and overcoming the earth’s inertia

Frame

Solid ash, natural, black or white lacquered, solid walnut or solid oak

Cushion

Fabric or leather

Dimensions (cm)

Width: 215

Depth: 75

Height: 70

Seat height: 42

[Translate to English:]

Das zweisitzige Gropius-Sofa F51-2 und das dreisitzige Sofa F51-3 entwickelten sich organisch aus dem kubischen Sessel F51 im Direktorenzimmer des Weimarer Bauhauses. Wechselnd stechen die schwebenden Polster ins Auge, ebenso wie die prägende Kragkonstruktion, die die Polsterelemente umfängt – man könnte auch sagen: durchdringt. Die Sofas F51-2 und F51-3 haben einen engen Bezug zu Tecta. Im Austausch mit Erich Brendel konnte dieser verantwortlich versichern, dass schon im Frühjahr 1920 der Sessel F51 im Direktorenzimmer stand, nicht aber das Sofa.

Von der Sofa-Gruppe selbst gab es nur wenige Fotos, die das Dreisitzer-Sofa dokumentieren. Axel Bruchhäuser von Tecta erinnert sich: „Es gibt ein Foto, das J. J. Pieter Oud, den niederländischen De Stijl-Künstler, dazu Wassily Kandinsky und Walter Gropius in der Mitte zeigt. Man brauchte detektivische Augen, um zu sehen, dass es das dreisitzige Sofa ist.“ Nach der originalgetreuen Reedition des Dreisitzers entwickelte Tecta auch den eleganten Zweisitzer.

Dabei wurde ebenso radikal das Programm der konstruktivistischen Moderne von Walter Gropius weiter verfolgt. Axel Bruchhäuser, seit 1972 Gesellschafter von Tecta, sieht darin Aufbruchsstimmung pur: „Dieser Anfang bei Null nach der totalen moralischen, materiellen und geistigen Zerstörung durch den Ersten Weltkrieg.

Durch die Bauhausgründung 1919 wollte er sich von alten Konventionen befreien, alles neu denken und vollkommen offen für das Neue sein.“ Dass dieses Neue inzwischen selbst fast ein Jahrhundert alt ist, muss man sich erst wieder ins Gedächtnis rufen angesichts dieses radikalen Aufbruchs in die Moderne.

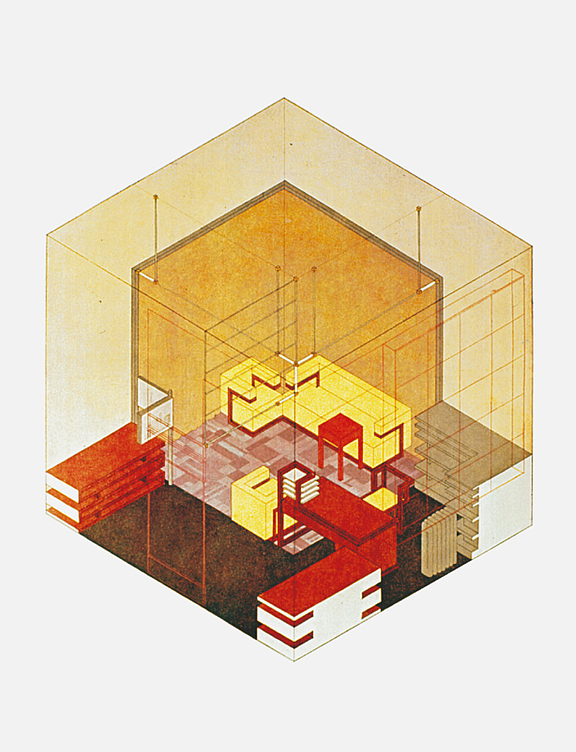

Besonders eindrücklich zeigt sich hier die im Bauhaus propagierte Idee des überkragenden Sessels, der Brücken schlägt bis hin zu El Lissitzkys Wolkenbügel von 1924. Das radikal Neue, hier ist es zu greifen. Walter Gropius sagt dazu: Das Ziel der modernen Architektur ist, „die Schwerkraft der Erde in Wirkung und Erscheinung schwebend zu überwinden.“ Genau das lässt sich hier erleben.

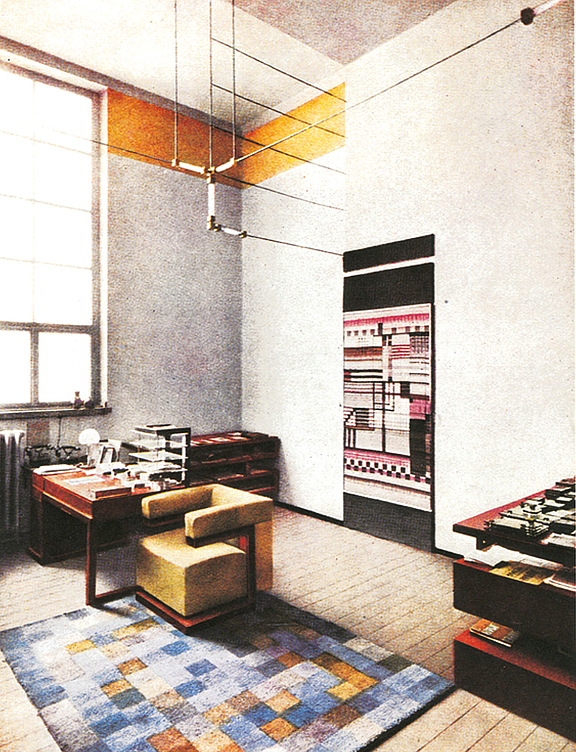

Gropius’ two-seater F51-2 sofa and the F51-3 three-seater version evolved organically out of the F51 cube armchair in the director's room of the Weimar Bauhaus. The floating cushions catch the eye alternately, as does the signature cantilever design which encompasses the upholstery – one could almost say, permeates it. The F51-2 and F51-3 sofas have close ties with Tecta. Erich Brendel corresponded with the company and was able to confirm that the F51 armchair already stood in the director's room in the spring of 1920, but not the sofa.

There only exist a few photographs of the sofa group itself documenting the three-seater sofa. Tecta’s Axel Bruchhäuser recalls: “There is a photograph showing J. J. Pieter Oud, the Dutch De Stijl artist, with Wassily Kandinsky and Walter Gropius in the middle. It took the eyes of a detective to see that it was the three-seater.” Tecta also developed the elegant two-seater following the faithful reedition of the three-seater. In doing so, it pursued the programme of Walter Gropius’ constructivist modernism with the same radicality.

Axel Bruchhäuser, a Tecta partner since 1972, sees this as the dawn of a new era: “They started at zero after the complete moral, material and intellectual destruction wrought by the Great War. By founding the Bauhaus in 1919, he wanted to free himself from old conventions, rethink everything and be completely open for anything new.” In view of this radical entry into modernity, we really need to keep in mind that this new movement itself is now almost a century old.

One of the most impressive concepts is that of the cantilever chair championed at the Bauhaus, which builds a bridge all the way to El Lissitzky’s Cloud Irons of 1924. The radically new assumes a tangible form. Walter Gropius said: The goal of modern architecture is “to defy gravity and overcome the earth’s inertia in impression and appearance.” And this is a living example.